We hosted a party on Sunday to watch the Bad Bunny concert...or the Super Bowl depending on which of us you asked. Of course this meant we spent the better part of Saturday cleaning every corner of our house. Whether it was the living room or a spot no one was sure to spend any time, it didn’t matter. Everything got a sweep, swipe, and spruce.

Why do I do that? No one has ever commented on the state of my home. No one expects it to look like a staged space from one of those home decorating shows. And yet, there I am, every time, with a mop, a bucket, and a bottle of Fabuloso.

The why behind my behavior can be described as my perceived motivation, or the function of my behavior. Everyone has a reason for doing the things they do. Your students are no different. It boils down to this: getting something or avoiding something, specifically activities, attention, or stimulus. Either a student wants first dibs on the basketball court, or she wants to get out of basketball drills altogether. On paper, naming the function of a student’s behavior seems easy enough.

And yet…

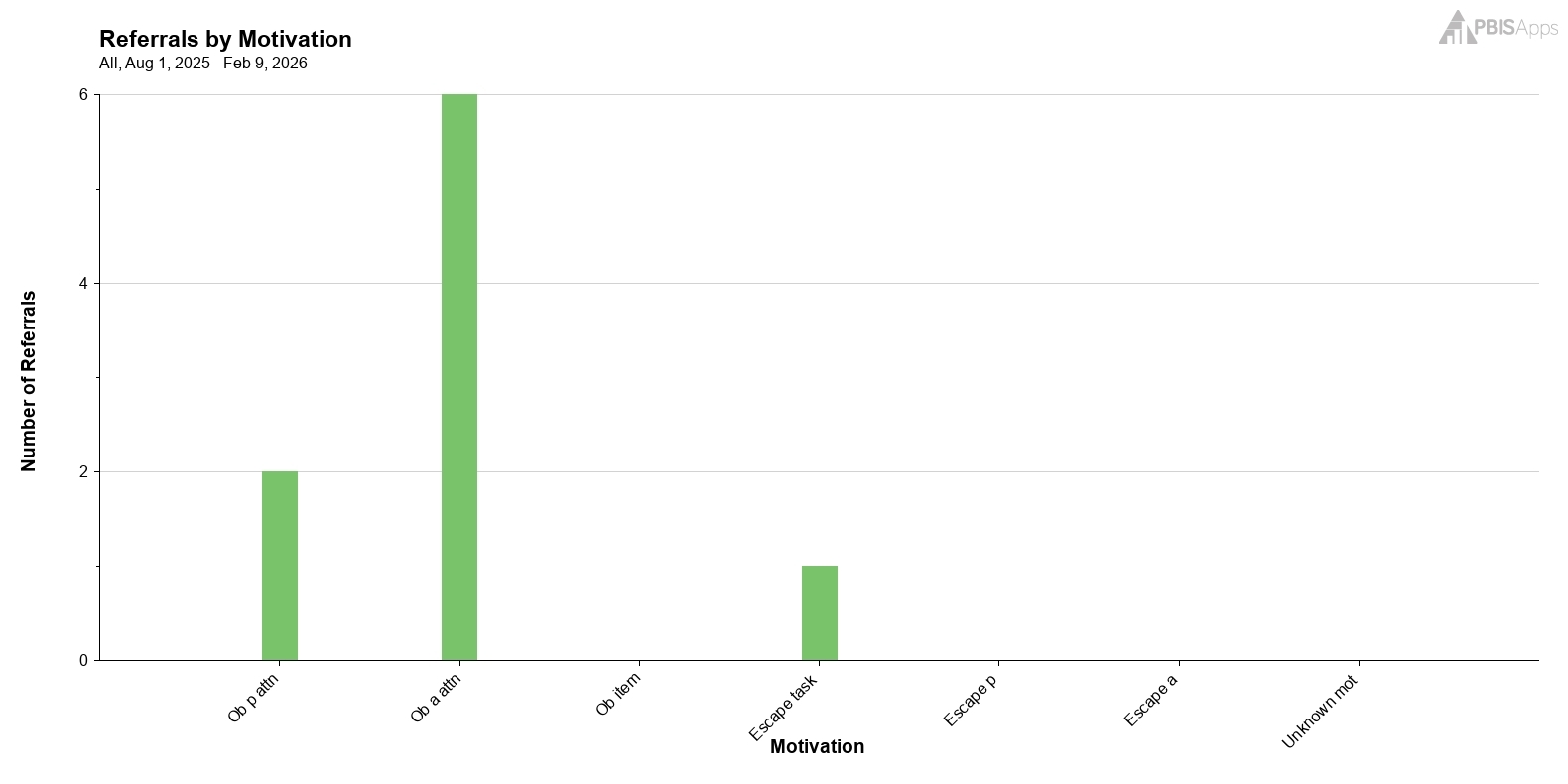

In the 2024-25 school year, there were 4,650,455 referrals written in the School-Wide Information System (SWIS). Of these referrals, around 29% listed Unknown as the perceived motivation of the student’s behavior. Maybe naming a behavior’s function isn’t as clear as it seems. Why?

Maybe it’s because we relate function of behavior to students receiving Tier 3 support. Maybe it sounds a little too research-y. Whatever the reason, we need to start considering it more regularly schoolwide. Let’s start this exploration where we find the formal version of function: functional behavioral assessments.

One referral does not create an entire intervention or plan…but each referral adds a piece of information necessary for understanding the function of a student’s behavior. It’s better to take your best guess than it is to leave that information out.

What is Functional Behavioral Assessment?

Part of the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA) requires schools to use functional behavioral assessment (FBA) to move away from exclusionary discipline practices like suspension and expulsion in favor of prevention-based practices.1

FBA is a process to understand behavior within a context. The process involves data collection from:

- Indirect measures like interviews and rating scales

- Direct observations

- Functional analysis to monitor targeted behaviors

Conducting an FBA for one student helps identify challenging behaviors, the events predicting when they’ll happen, and how those behaviors and events might vary across time. Ultimately, the information we gather during an FBA builds behavior support plans that are more successful, informed, and contextually relevant.

The detail you get from a formal FBA is incredibly useful, but its formality makes it seem like determining function is better left for specialists to figure out.

It doesn’t have to be.

Function-based thinking happens all the time, maybe without even realizing it:

- When you plan a transition activity because you anticipate high-energy behavior coming in from recess, you’re thinking about function.

- When you enroll Jackson in Check-In Check-Out because you know he loves to connect with adults at school, you’re thinking about function.

- When you make sure Andrea has a comfortable (non-distractable) place to sit because she gets a little squirely during independent reading, you’re thinking about function.

Not every student needs a comprehensive FBA, but all students can benefit from function-based support. Enter: Basic FBA.

What is Basic FBA

Basic FBA is a proactive approach to behavior support planning that relies on simplified FBA procedures. It operates from the idea that anyone can learn how function works and use that information to build interventions. While complex student behaviors require formal FBA, Basic FBA works well for students whose behavior is:

- Persistent

- Low-Level

- Non-dangerous

- Occurring during just one or two routines in the day

- Inadequately addressed with current Tier 2 support2

Basic FBA makes assessing function a more integrated part of your schoolwide community and gets students the support they need faster.

Let me guess. At this point, you’re wondering: What does research say about this? I’m so glad we’re on the same page.

After 10 staff members received four hours of Basic FBA training, they were able to name the function of each student’s behavior so accurately that behavior specialists could trust their assessment to guide an individualized behavior intervention.3 The study also found that using function-based logic schoolwide might reduce the number of more complex, resource-intensive support plans overall.

Dearest Reader: At this point, if you’re looking for where you can receive Basic FBA training, you should know it’s available online, right now, for free! The pacing is self-guided, the activities mimic actual school experiences, and there’s a certificate at the end declaring you trained!

If the referral patterns at your school come with a lack of information about perceived motivation, maybe it’s time to take function-based thinking out of your Tier 3 support team and spread it around schoolwide. Here are some of the ways you can kick start the effort and get everyone on the motivation train.

Know Your ABCs…

…Or in this case, Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence. Before you can expect everyone to participate in collecting motivation data, you need to get everyone using a common language. The ABCs are fundamental.

Antecedent: the context where the behavior is most likely to happen. It’s the combination of a place (routine) and an event (trigger) creating the perfect scenario for a certain behavior. Meet me in a conference room at work after I just edited a technical document and you’ll get a different set of behaviors out of me than if we’re at a happy hour enjoying the patio on a sunny Friday afternoon. The same is true for student problem behaviors; they’re more likely to happen in specific contexts. This is the Antecedent.

Behavior: something you can observe and describe to someone else so they would recognize it when they see it. It’s the difference between saying a student was disruptive, which could be any number of behaviors, and saying the student yelled across the room.

Consequence: what happens directly after the behavior. It could be the student goes to the office; it could also be other students laughing at the joke someone just told. The consequence to notice is the one most meaningful to the student.

Identifying the ABCs gives other people the full picture of how an incident unfolded. When you document a behavior in SWIS, you share these ABCs.

- Location and Time give you the basics for an Antecedent

- Operationally defined, mutually exclusive behavior categories give you the specific Behavior

- Action Taken tells the team the primary Consequence delivered

Use It in a Sentence

This is my favorite strategy from the modules: Insert the ABCs in a sentence, mad-lib style, and you get the context. (Note: The routine plus the trigger create the antecedent.)

During [insert routine], when [insert trigger], the student [insert observable behavior] and as a result [insert consequence].

Completed, the sentence might look something like this:

- During math, when I assigned a multi-digit multiplication worksheet, Martin broke his pencil and put his head on his desk, and as a result, I walked over to his desk and helped him get started.

- During reading, when students are doing independent work, Ella whispered something to two other students, and as a result, her friends laughed and kept talking to her.

The sentence organizes the antecedent, behavior, and consequence to create meaning and maybe even elicit a connection you didn’t notice as everything happened in the moment. The context where the behavior occurs leads us straight to function. You could even consider writing this mad-lib sentence into the Notes field in SWIS when you add a referral for a student engaged in the Basic FBA process.

Look for Patterns

Asking teachers to take a best guess at a student’s perceived motivation when they’ve never thought about it before might be a big ask.

“What if I guess and I’m wrong?”

“What if my student is doing this for a totally different reason?”

Walking through the modules, I felt this feeling distinctly in section six of the first module. I wrote an office discipline referral (ODR), including my best guess at the student’s perceived motivation, based on a video example. I second-guessed myself a few times before deciding on Avoid Task. In the very next slide, the referral I wrote appeared next to several other referrals the student received for similar behaviors. Even though my referral didn’t identify the same motivation as the others, there was an observable pattern.

The lesson here is this: One referral does not create an entire intervention or plan…but each referral adds a piece of information necessary for understanding the function of a student’s behavior. It’s better to take your best guess than it is to leave that information out. By the time a team refers a student for additional support, there will already be a history of the possible motivation behind their behavior. Your best guess makes it so much more efficient for teams to access the data they need in SWIS and for students to get the support they need faster.

At the end of the day, understanding motivation isn’t about getting it perfectly right on the first try. It’s about paying attention to the context where the behavior happened and thinking about what might make it happen again. When all of us start thinking this way, we move from reacting to behavior to responding with intention. Your best guess at motivation, adds a piece to the puzzle and brings us all closer to designing supports that actually work for students. The more we normalize function-based thinking, the better equipped we are to support students before challenges escalate.